It’s become a cliche’ of sorts.

A former sports star retires and finds work in the radio or TV booth of his or her former team. It doesn’t matter if said athlete brings anything to the table. The resume reads, ‘former athlete.’ You’re hired!

Walt Frazier never saw himself as the athlete-turned-color commentator.

He had learned some tough lessons at Southern Illinois. Frazier used it as motivation to reach his full potential as a player and — more importantly — as an educated man.

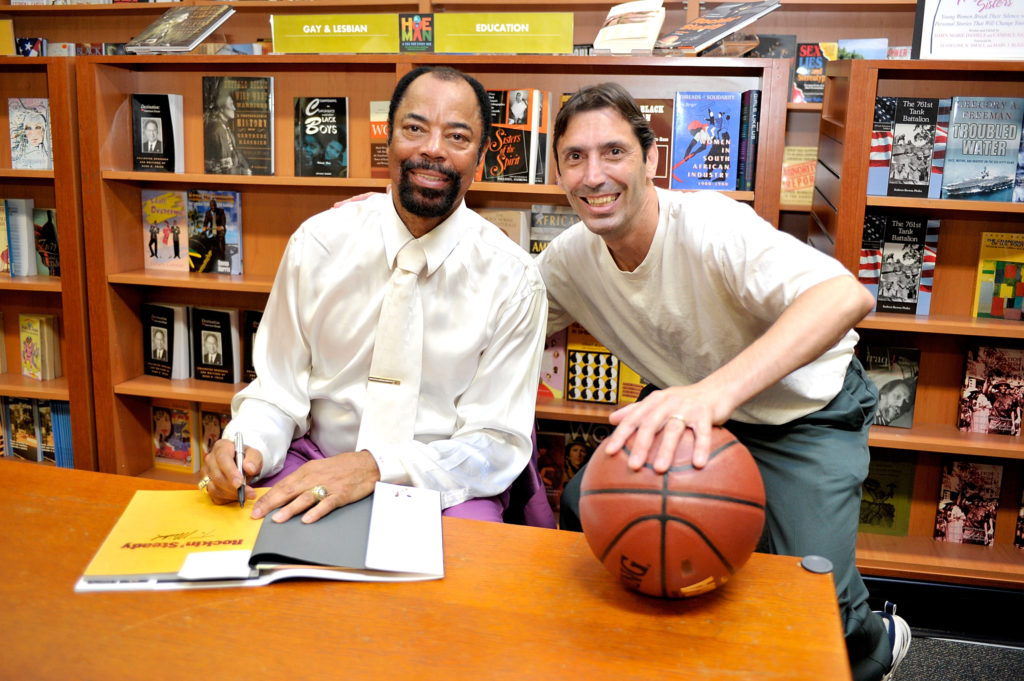

So how in the world did the man Knicks fans have affectionately come to know as “Clyde” become one of the most colorful and insightful commentators in sports?

“It was serendipitous,’’ said Frazier, using his favorite of all words.

Some fans weren’t alive when Frazier helped lead the Knicks to NBA titles in 1970 and 1973. They never saw him play his shrewd, gunfighter-quick defense, but they do see the flamboyant outfits and hear the commentary that is just as colorful.

“I hear kids say, ‘Hey dad, there’s the Knicks’ announcer,’’ Frazier told MSGNetworks.com. “There’s the guy with the suits. The funny suits. The crazy suits.’’

Frazier’s combination of eccentric fashion style and dynamic verbiage (did I use the proper word, Clyde?) has made him a unique presence in front of and behind the mic. He might be more of fan favorite today than in his glory days as a Knick. And glorious they were.

Frazier posted the best NBA Finals game in franchise history when he scored 36 points (including 12-of-12 from the line) and had 19 assists in Game 7 of the 1970 series-clinching win over the Lakers that gave New York its first title.

As a broadcaster, Frazier’s rhyming, sing-song, analytic style has made him a Harry Caray-like beloved figure in the Big Apple. Who has watched the Knicks go on a run and not heard “dishing and swishing” in their head?

Yet Frazier’s rise to prominence on-and-off the court have not come without, what Clyde might describe as, trials and tribulations.

Frazier took the first steps toward both careers at Southern Illinois. He learned the hard way, which made last weekend’s 50th anniversary of the Salukis’ 1967 NIT championship team all the more sweeter.

Frazier was the MVP of that tournament, which at that time was more prestigious than the NCAA Tournament. In fact, Southern Illinois turned down an invitation to play in what could have been referred to as the Little Dance back then.

“I honed my skills here in Southern Illinois,’’ Frazier said Friday night at the reunion in Carbondale, Ill. “Going to the NIT catapulted me into the national spotlight, being the MVP and being drafted by the Knicks. It was a culmination of those things that I will never forget.’’

Carbondale might sound small-town to New Yorkers, but for Frazier, who was born and raised in the segregation of the Deep South, he learned lessons big and small.

The most important lessons came in the classroom and on the defensive end of the court.

Frazier was academically ineligible to play as a junior. He could practice with the team, but coach Jack Hartman would only allow Frazier to practice on defense.

As for academics, Frazier was left to make it on his own.

“That was the making of Walt Frazier because nobody helped me,’’ Frazier said. “The coaches didn’t help me. I had to do everything myself. I registered my classes. I had to find my housing. I had to do everything.

“That’s when I grew up as a person. I started to take on my responsibilities. I developed discipline. I always look back on that one year of adversity in my life as a really positive experience.’’

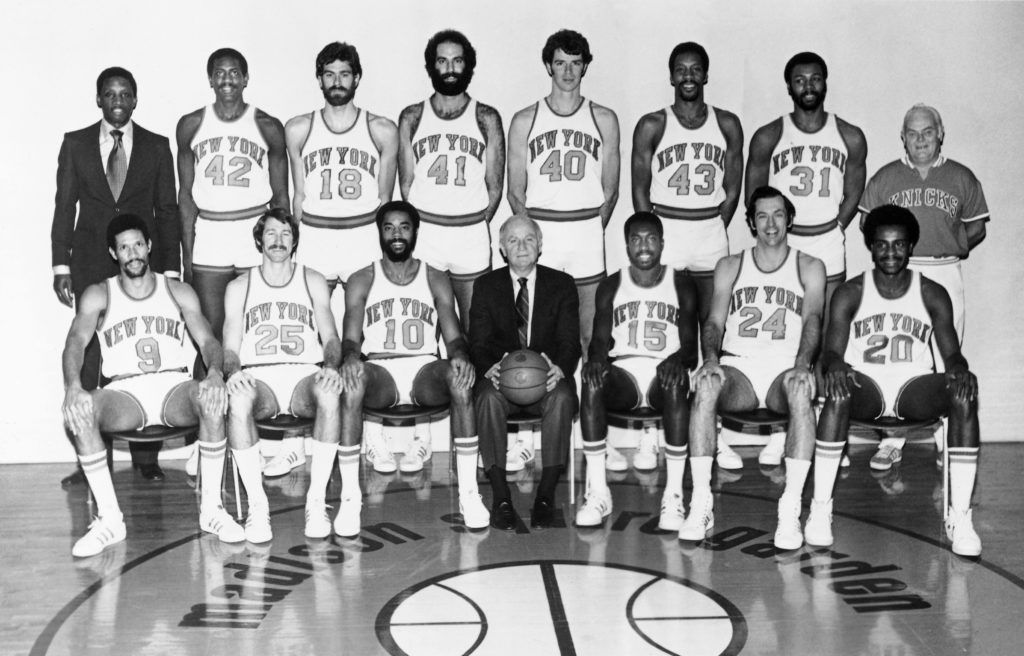

His experience in the NBA couldn’t have been more rewarding. Frazier’s teams, under legendary coach Red Holzman, epitomized teamwork on both ends of the court. The Knicks reeled off a then NBA-record 18 straight wins in the 1969-70 season.

Frazier, who came to New York wearing penny loafers and button-down shirts, had a teammate in Dick Barnett, who was a sharp dresser.

Frazier took note. He would go on to take a lot of notes.

He studied Willis Reed’s penmanship because it was cleaner than Frazier’s. He studied opposing player’s offensive games because when you practice defense and only defense for an entire season, you learn about tendencies and preparation.

“I fell in love with defense,’’ Frazier said. “Defense became my favorite part of the game. So, I mastered the stance, the technique, everything.’’

The same can be said of his broadcasting style.

He learned the hard way, doing pregame and postgame shows with Greg Gumbel, which were easy. But when it came to halftime segments on the court, Frazier was caught off guard.

“Fans are saying, ‘Hey Clyde, can I get an autograph?’’’ Frazier said. “They’re blaring music and I’m trying to find the monitor. So the Knicks used to send me to Marty Glickman to critique me and the first time he critiqued me, he [ticked] me off.

“He goes, ‘Clyde, look at you, you look like a pickpocket,’ cause I was looking for the monitor and looking around.

“He said, ‘When you do radio, you’ve got to assume people are blind and they can’t see.’ So you’re not on the baseline, you’re on the left baseline. You’re at the top of the key, the circle. You had to be descriptive.’’’

And quick. Frazier was teamed with Jim Karvellas in 1989 on WFAN Knicks’ radio broadcasts and learned to say it fast and make it count.

“Karvellas wouldn’t allow you to say much,’’ Frazier said. “He used to do [Baltimore] Bullets games by himself. He was old school.

“I would start talking and he would ride right over me. That when I started rhyming, sometimes all I could get in was, ‘swishing and dishing.’’’

And he was criticized for it. Like many trailblazers, Frazier’s style was dubbed a shtick. Shtick this. Frazier was working tirelessly to master his new craft.

He bought the Sunday New York Times mostly to read the Arts & Leisure section. The reviews on plays often used words such as — wait for it — “mesmerizing.”

Throw in words such as riveting, provocative, dazzling and Frazier was building his vocabulary. He has countless books on words and phrases.

He would have his girlfriend overnight tapes when the Knicks were on a West Coast swing so he could review them on the flight home.

He began watching telecasts of other games with the sound off, forcing him to be more attentive. And he started watching soccer and other non-mainstream sports, picking and choosing phrases he could apply to Knicks telecasts.

His girlfriend at the time was an English major, which is kind of like an arsonist dating a firefighter.

“She used to call me, ‘The Word Man,’ because I was always asking her, ‘How do you pronounce this word or that word?’’’ Frazier said. “Sometimes she’d see me coming and she’d run into another room.’’

The perception that Frazier was a sideshow rather than a professional color commentator irked the man who always has a smile and kind word.

He equates the easiness with which he offers up his unique color commentating to the ease with which NBA players make shots. It’s not an accident.

“It’s like when they see these players at The Garden, they see them for two hours, they think it’s easy,’’ Frazier said. “They see [Steph] Curry and they think, ‘Oh man this guy’s just throwing in shots.’

“They don’t see the hours and hours these guys put into perfect that. So in the beginning, people said it was shtick because I didn’t know the game. That’s why he’s doing the rhymes.’’

Clyde is enjoying the last laugh.

He owns property in Harlem, an escape haven in St. Croix, has lucrative endorsement deals and a commentating career that is, as he would say, often imitated but never duplicated.

His fashion style, he says, is still evolving. His first trademark was the fedora hat, which Warren Beatty made famous in the movie, “Bonnie and Clyde.’’

Clyde was born.

It wasn’t until he saw Mark Jackson and Patrick Ewing getting their suits custom made at Mohan’s Custom Tailor that Clyde saw his opening. Clyde walked in and told proprietor Mohan Ramchandani:

“Man, these guys can’t sell suits,’’ Frazier said. “I’m Clyde. I’m the guy you need. This guy, Mohan, he didn’t know me. He said, ‘Who is this guy?’ Then he finally found out who I was.’’

Who is Walt “Clyde” Frazier?

Is he an individualist with a twist? We’ll leave that to Clyde.

“Words are like people,’’ Frazier said. “The more you see them, the more you know them.’’