It was 90 years ago that the Rangers played their very first hockey game. The date was Nov. 16, 1926, and the opponent was the defending Stanley Cup champion Montreal Maroons.

But how did the Rangers come into the league in the first place?

The Blueshirts were granted a National Hockey League franchise prior to the 1926-1927 season. They would play at what actually was the third version of Madison Square Garden, located on 8th Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets.

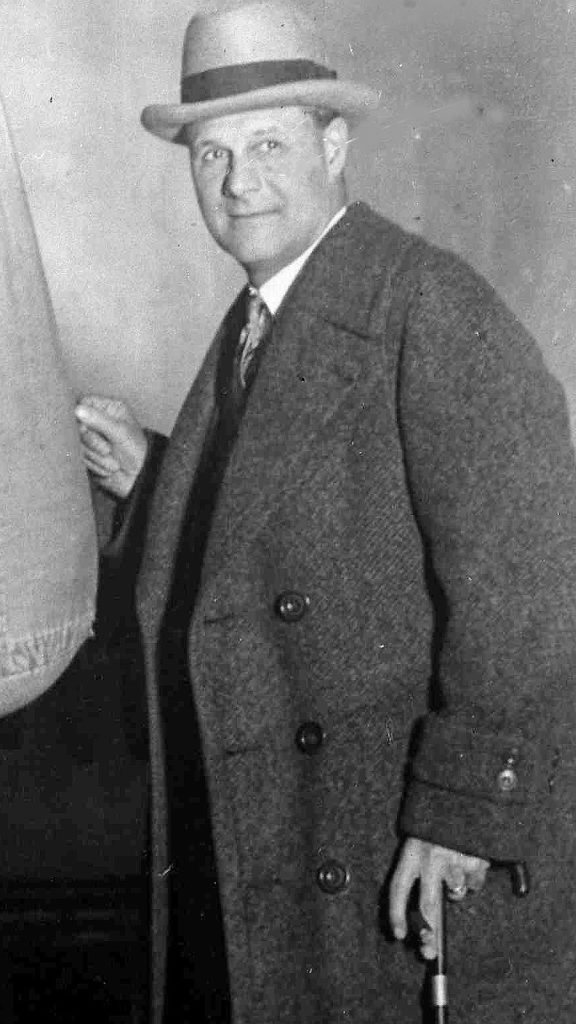

The new team became known in the press as “Tex’s Rangers” after Madison Square Garden III founder George Lewis “Tex” Rickard, so the team simply dropped the Tex and that was that. “Rangers” it is!

Now, all Rickard had to do was put a competitive team together from scratch; one that could go skate-to-skate with the Star-Spangled New York Americans who already had played a year of NHL hockey at The Garden.

Not a hockey man, MSG president John Hammond was wise enough to realize that he didn’t know enough about the ice game to independently build a brand-new NHL club.

Several potential managers were suggested to Hammond. One was Lester Patrick and another was Constantine Falkland Karry’s Smythe — otherwise known as Conn. Smythe was a galvanic, young Torontonian who, according to the Colonel’s touts, knew everything there was to know about building a franchise from scratch.

A World War I hero, Smythe had started as an artilleryman, but in 1917 switched to flying. He was shot down at Passchendaele, Belgium and wound up in German prison camps. Following the Great War, he was both a successful businessman as well as organizer of championship collegiate hockey teams in his native Toronto.

Early in 1926, Smythe coached the University of Toronto varsity hockey team to the Canadian Intercollegiate championship and a place in the Allan Cup final for the senior championship of the dominion. Smith’s sextet lost the Allan Cup battle to Port Arthur, Ontario, but Conn already had impressed Boston Bruins owner Charles Adams enough to persuade the latter to phone his pal Hammond in New York.

“There’s a fellow called Smythe in Toronto who brings in college teams that are just as good as my Bruins,” said Adams. “He knows all the good, young collegiate players; why don’t you give him a try?”

Adams’ word was good enough for Hammond. Immediately after the Allan Cup tournament concluded, Hammond invited Smythe to New York. The Colonel was impressed with the cocky, little Canadian and signed him for several years plus expenses. According to the pact, Smythe would deliver the players and then manage them in their first NHL season.

“It was the chance to move into big-time hockey that I had been waiting for,” said Smythe. “I knew every hockey player in the world right then. I had been going to Toronto St. Patrick’s (NHL) games and was familiar with players on the seven NHL teams. Also, I had a pretty good line on players in the Western Hockey League.”

“But the real edge I had on the other NHL managers was that for years I’d been coaching amateur hockey, watching men on the way up. Some who were playing senior or semi-pro hockey, I knew, were good enough for the NHL.”

Remarkably, Smythe never lasted to opening night. Battles with Hammond never were amicably resolved and Smythe was fired and replaced by Lester Patrick.

In mid-October 1926, Hammond dispatched the following telegram to Lester Patrick in Victoria:

“WOULD LIKE TO HAVE YOU AS COACH OF THE RANGERS STOP IF INTERESTED PLEASE WIRE ACCORDINGLY AND I WILL ARRANGE IMMEDIATE TRANSPORTATION TO NEW YORK FOR FULL DISCUSSION STOP JOHN HAMMOND.”

Lester accepted and headed for New York via train, while Hammond checked out his team in Toronto.

The loss of Smythe could have been a tragedy for the Rangers because he was and would continue to prove himself a hockey genius. But the arrival of Patrick was a bit of uncanny luck since Lester, too, had one of those rare hockey brains, and proved it as soon as the 1926-27 season got underway. By the halfway point in the campaign, the Rangers were on top of the five-team American section of the NHL with a 12-7-3 record, while the Americans held third place in the Canadian section with an 11-12-0 mark.

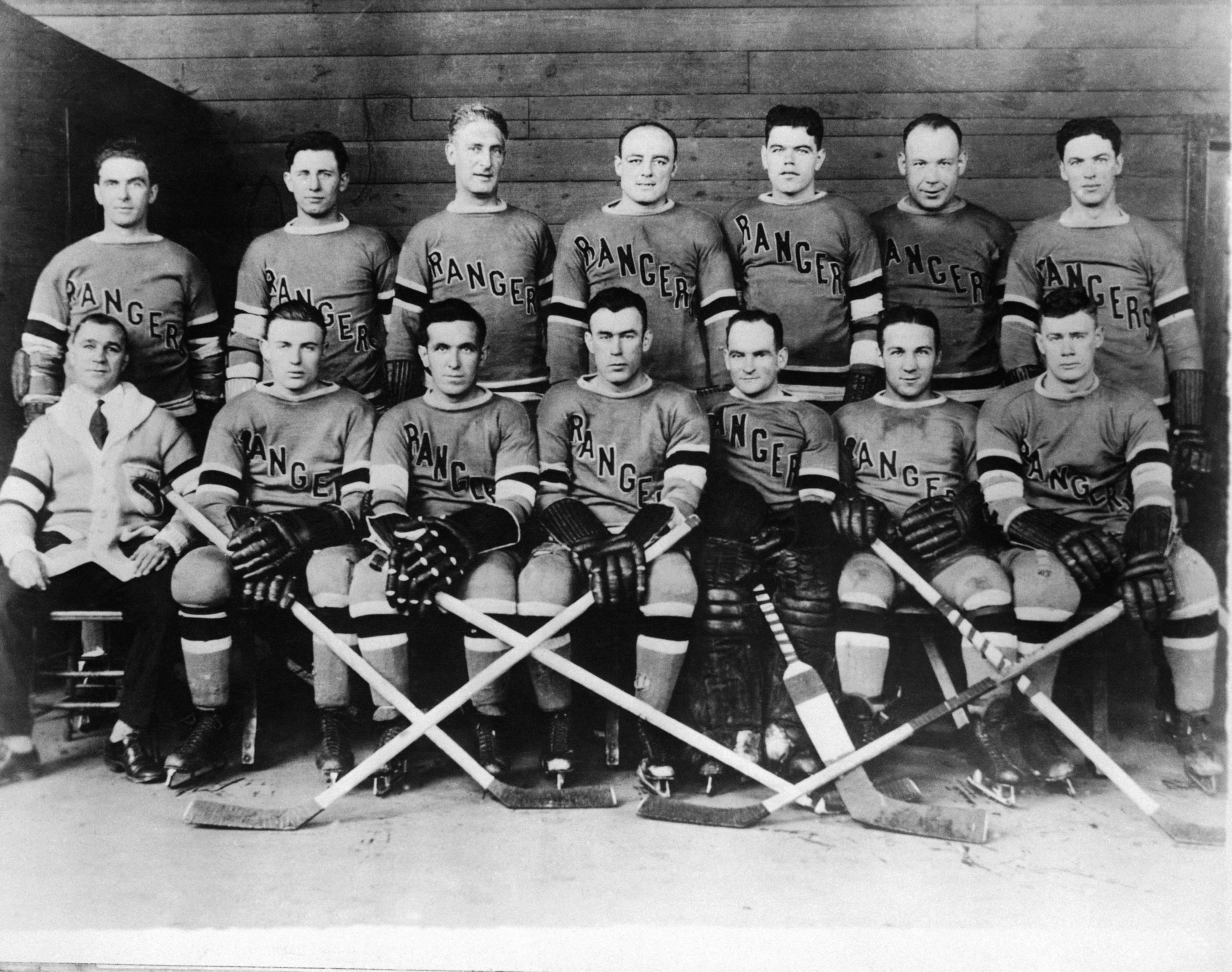

Much of Patrick’s success could be credited to Smythe, who had assembled most of the Rangers before he left training camp. The first line, featuring stylish Frank Boucher at center between the Cook brothers, Bill and Bun, took the league by storm, with right wing Bill eventually emerging as the league’s leading scorer in that rookie year for the Rangers.

Hal Winkler and Lorne Chabot split the goaltending for New York. Ching Johnson and Taffy Abel were the rocks on defense. Johnson’s rugged style was a marvel to friend and foe alike. The Boston Bruins’ ace defenseman Flash Hollett put it this way:

“That Johnson was a huge man with arms and legs like trees,” said Hollet. “He had a way of standing with his arms out and stick extended, a style no one else had copied, and he seemed to cover half the rink. One of my Bruins teammates, Leroy Goldsworthy, could never get around him and he used to say: ‘It’s just like going home to my mother. Every time I run into Johnson his arms are open.'”

There were many scintillating skaters on that first Rangers team, but none captured the imagination of The Garden crowd like the brothers, Cook and Boucher. They moved across the rink with the grace of figure skaters and passed the puck with radar-like accuracy. It was difficult to choose among them. Bill was the crackerjack shot, Bun had the brawn and Boucher all the class in the world.

“Boucher became a center such as the league seldom has known,” wrote Dink Carroll of the Montreal Gazette, “and a darling of the gallery gods and of the rich folk in the promenade seats as well. He would take the puck away from the enemy with the guile and smoothness of a thief picking the pockets of yokels at a county fair, then whisking it past the enemy goaltender or slipping it to Bill of Bun.”

Boucher was without question the cleanest player ever to lace on a pair of skates in the NHL. He won the Lady Byng trophy (for excellent, gentlemanly play) so many time — seven in eight seasons — the league finally gave it to him.

Oddly enough, the one fight Boucher had in his entire NHL career took place in the first game on Garden ice against the bullying Montreal Maroons, the Stanley Cup champions. “They were big,” wrote New York Times columnist Arthur Daley, “and they were rough. Every Maroon carried a chip on his shoulder.”

The chips became heavier when Bill Cook took a pass from brother Bun and scored what proved to be the only goal of the night. Fortified with a one-goal lead, the Rangers began counter-attacking with their bodies and fists. Johnson would drop a Maroon to the ice and then grin his very special trademark smile that delighted The Garden crowd. The huge Abel hit every Montreal player in sight, and soon the rink was on the verge of a riot.

Up until then, the gentlemanly Boucher, who had once been a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, had minded his business and stayed out of trouble. But “Bad” Bill Phillips, one of the most boisterous of the visitors, belabored Boucher with his elbows, knees, and stick at every opportunity. “The patient Boucher,” wrote Daley, “endured the outrages until a free-for-all broke out.”

At that point, Boucher very discreetly dropped his stick, peeled off his gloves, and caved in Phillip’s face with a right jab. The Maroon’s badman slumped to the ice, whereupon Boucher politely lifted him to his feet … and belted him again. When Boucher lifted Phillips for the second time, the Montrealer grabbed his stick and bounced it off Boucher’s head, thus ending the fight.

The Rangers defeated the Maroons, 1-0, on Bun Cook’s goal. As for the atmosphere on opening night nine decades ago, here how author Eric Whitehead described it in his book, The Patricks: Hockeys Royal Family:

“Movie star Lois Moran minced scenically out for the ceremonial face-off, and after dropping the puck between the two rival counterman, Stewart and Frank Boucher, the lady was escorted back to her seat behind the Rangers’ bench.”

Wrote Ed Sullivan, the young Broadway reporter who chronicled the item in his next day’s “Talk of the Town” column: “Miss Moran was in the elegant company of Mayor Jimmy Walker and his beauteous companion of the evening, actress Betty Compton…”

Not surprisingly, opening night was a dazzling success for the brand new Rangers and the Blueshirts have carried that tradition for nine exciting decades.