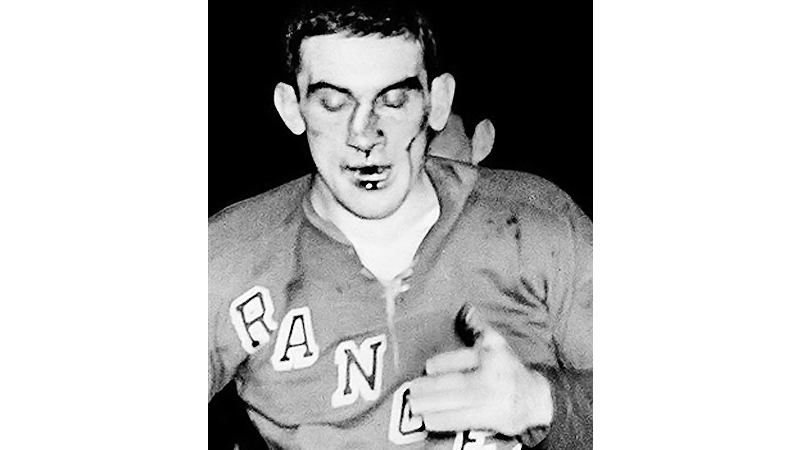

Put it this way, if Lou Fontinato were playing defense for the New York Rangers today, he would have been one of the most popular — if not the most popular — athlete in New York.

I speak firsthand since Louie and I grew up together in the Rangers organization. During the 1954-55 season, I worked in the Blueshirts publicity department and Fonty was a hell-for-leather rookie.

This wonderful man, who for many NHL years seemed indestructible, died at the age of 84 on Sunday near his birthplace in Guelph, Ontario.

What made Fontinato so special was a blend of uncontrolled exuberance, passion, lust for body checking and — not to be underplayed — delight in good old fist-fighting.

When Louie fought, The Garden — then on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets — would go mad.

“As long as I knew Louie,” said Hall of Famer Andy Bathgate, “he loved a good fight. But he also was a first-rate defenseman, even in Juniors.”

Bathgate, who recently passed away, originally teamed with Fontinato on the Rangers Junior farm club, the Guelph Biltmore Mad Hatters.

Playing in the Ontario Hockey League, the Biltmores went on to win the Memorial Cup in 1952, emblematic of the Canadian Junior championship.

In addition to Fontinato and Bathgate, such Bilts as Dean Prentice, Harry Howell and Aldo Guidolin all graduated to the Rangers in the early 1950s.

“We needed time to adjust from Juniors to the NHL,” Guidolin once explained, “and at first it was tough for all of us. Prentice and Howell were able to stick but guys like Louie had to spend some time in the minors before they were ready.”

Alternating between the Rangers pro farm clubs in Saskatoon and Vancouver, Fontinato rapidly established a two-fisted reputation that was guaranteed to win the hearts of Big Apple ice fans.

“I couldn’t wait for the club to promote him,” former Rangers publicist Herb Goren once told me. “I knew that once Louie got here at The Garden that he’d be a hero.”

Plus he had a nickname to go with his rep. In fact, to this day it’s debatable whether Goren gave Fonty his permanent nicknames — Leapin’ Louie or Louie The Leaper — but both stuck.

The “leaping,” by the way, took place when a referee slapped him with a penalty. Easily outraged, Fontinato would jump off the ice but by the time he landed he still wound up in the sin bin.

How important was Lou to the Rangers?

From 1951 through 1955 the Blueshirts missed the playoffs four straight years. When Fontinato became a full-time Ranger for the 1955-56 season, the club made the playoffs that year and emerged as one of the NHL’s best outfits.

Smaller Rangers such as sharpshooter Camille (The Eel) Henry and playmaker Don (Bones) Raleigh felt more confident with their “cop” Fontinato to protect them.

“It was reassuring to know that we had a tough guy like Louie,” Henry once told me. “He was our enforcer.”

As press agent Goren had predicted, within one full year at The Garden, Fontinato became the undisputed favorite of the gallery gods.

One of them was Hal Gelman, a member of the Rangers Fan Club and one of Louie’s pals. A Rockland County insurance broker, Gelman remained in touch with Fontinato long after Louie retired from hockey.

“Last year I spoke to him at his cattle farm in Ontario,” Gelman told me, “and he sounded upbeat. I’m shocked over the news.”

“When I think about Louie as a player, the first thing that comes to mind is his fight with Rocket Richard.”

Montreal’s most feared scorer, Maurice Richard was a frequent Fontinato target. On one Sunday night visit by the Canadiens to The Garden, the pair went at it in a memorable bout.

“It was even,” Gelman remembered, “until Louie connected with a right to Rocket’s head. Richard already had a patch on his forehead from a previous injury and Louie’s punch opened the wound and blood spurted out like an oil well.”

The bout and subsequent uproarious Rangers victory inspired legendary New York Herald-Tribune columnist Red Smith to headline his story ROMAN CIRCUS.

Usually paired on the blue line with Harry Howell, Fonty was part of a solid defense that also featured Jack (Tex) Evans, John Hanna and the late Bill Gadsby.

Unfortunately, their road to the Stanley Cup inevitably was blocked by the Canadiens who were in the process of becoming the only club ever to win five Cups in a row (1956-1960).

Although the NHL never indulged in crowning a “Heavyweight Champion,” it was generally agreed by the late 1950s that Fontinato won more fights than anyone — and then Gordie Howe came along.

Howe, the Red Wings immortal who recently passed away, had reached his physical prime in the 1958-59 season as did Fontinato. They had jousted a few times before but their scrums were broken up before any damage was done.

Not this time. On February 1, 1959, what many considered “The Hockey Fight Of The Century” took place at The Garden and I viewed it from the press box overhanging the mezzanine.

What became a vicious bout began innocently enough with Howe and Rangers pest Eddie Shack high-sticking behind the New York net. Camped at the left blue line, Fontinato seemed to think that his teammate needed help.

At that point, Louie moved swiftly from his outpost at the blue line. The distance from the blue line to the fight site was about 70 feet, which the Ranger policeman negotiated in seconds.

The circumstances were perfect for Fontinato. In most of his fights, he would defeat opponents by a surprise attack, raining blows on them before they could muster a defense.

But Howe saw Louie coming, even though Fontinato knocked him off balance and discharged a flurry of punches that normally would have sent an opponent reeling for cover.

Unfazed, Howe seemed to be sizing up Fontinato. Then, the counterattack began. Howe’s short jabs moved like locomotive pistons, wounding his foe around the nose and eyes. Clop! Clop! Clop!

At about this time the linesmen moved in to halt the brawling but nobody wanted to get near the punches. Fontinato returned with a few drives to Howe’s midsection but Howe ignored them.

The once fearsome Ranger had been mashed almost beyond recognition. His nose was broken at a right angle to his face which was dripping with blood. Only one factor saved him from complete disaster– he wasn’t knocked down.

Anyone who had doubts about the winner merely had to check the photos, including one in Life magazine which showed Lou’s nose at a distorted angle. The Ranger required surgery that night and — for all intents and purposes — he no longer was the NHL Heavyweight champ.

Some believe that Louie got a bum rap. Publicist Goren insisted to me: “Everybody ignored all the solid blows Lou delivered to Howe’s body. They did plenty of damage.”

In a conversation about the bout with Gelman last year, Fontinato argued that the bout ended in a draw. “Everybody thinks Gordie won,” said Lou. “Nobody realizes what I did to him. I ripped him pretty good and bloodied his eye. No way he won that fight.”

Writing in “Players, The Ultimate A-Z Guide Of Everyone Who Has Ever Played In The NHL” author Andrew Podnieks, added this comment: “Lou said the fight was a draw. Howe’s unscratched mug suggested differently.”

Fontinato remained a popular Ranger despite the fight results and in 1960-61 still was an effective backliner. The perfect New Yorker, Lou loved to mix with fans of all kinds. I often had him over to our house in Williamsburg where he feasted on my grandma’s Hungarian goulash.

One of his favorite eateries was an Italian restaurant near the Brooklyn Navy Yard under the Myrtle Avenue El. Louie knew he was the most popular Ranger and wanted to be paid for it.

When it came time to talk contract with General Manager Muzz Patrick after the 1960-61 season the conversation was succinct.

Lou: “I want a raise.”

Muzz: “You’re not getting one.”

Lou: “Then trade me.”

And so Patrick did — to of all teams the Montreal Canadiens. Louie adjusted to his new surroundings in the 1961-62 season after which tragedy struck, ending his hockey career.

During a game with the Rangers at The Forum on March 9, 1963, New York’s Vic Hadfield charged Louie at the far right corner of the rink. Anticipating the blow, Louie “submarined” and Hadfield went over the Blueshirt.

But in so doing, Hadfield at least partially missed the check but somehow, in the collision, Lou’s neck was broken and he never played hockey again.

Off the ice, Fontinato always knew how to budget and make a buck. His best move was investing in a highly-lucrative 265-acre cattle farm in Ontario which he eventually maintained by himself.

Occasionally, Lou would show up at a hockey venue, including The Garden, and maintained contact with some close friends from his playing day; Hal Gelman being one of them.

“What can I say?” Gelman concluded when told about Fontinato’s death. “He was a terrific player to watch and a great guy to know. I’ll sure miss him.”

Ditto for me and for the legion of Rangers fans still around who had the pleasure of watching Leapin’ Louie — win or lose, the epitome of Old-Time Hockey.